New songs can be both exciting and frustrating when it comes to writing drum beats. It depends on the expectations in the room as well as your own ideas about what makes the right drum beat for the song. I’ve thought about this for years and wonder if there are some things I consider that may help other drummers through this process.

The hierarchy of considerations starts with a bunch of questions about the gig. Whose songs? Are you being paid? Is there a producer who is known for providing extensive input while writing drum beats? Is it just a jam with no expectations for the drum beat beyond the obvious need for one that works? These are just some of the things I consider when writing drum beats for new songs.

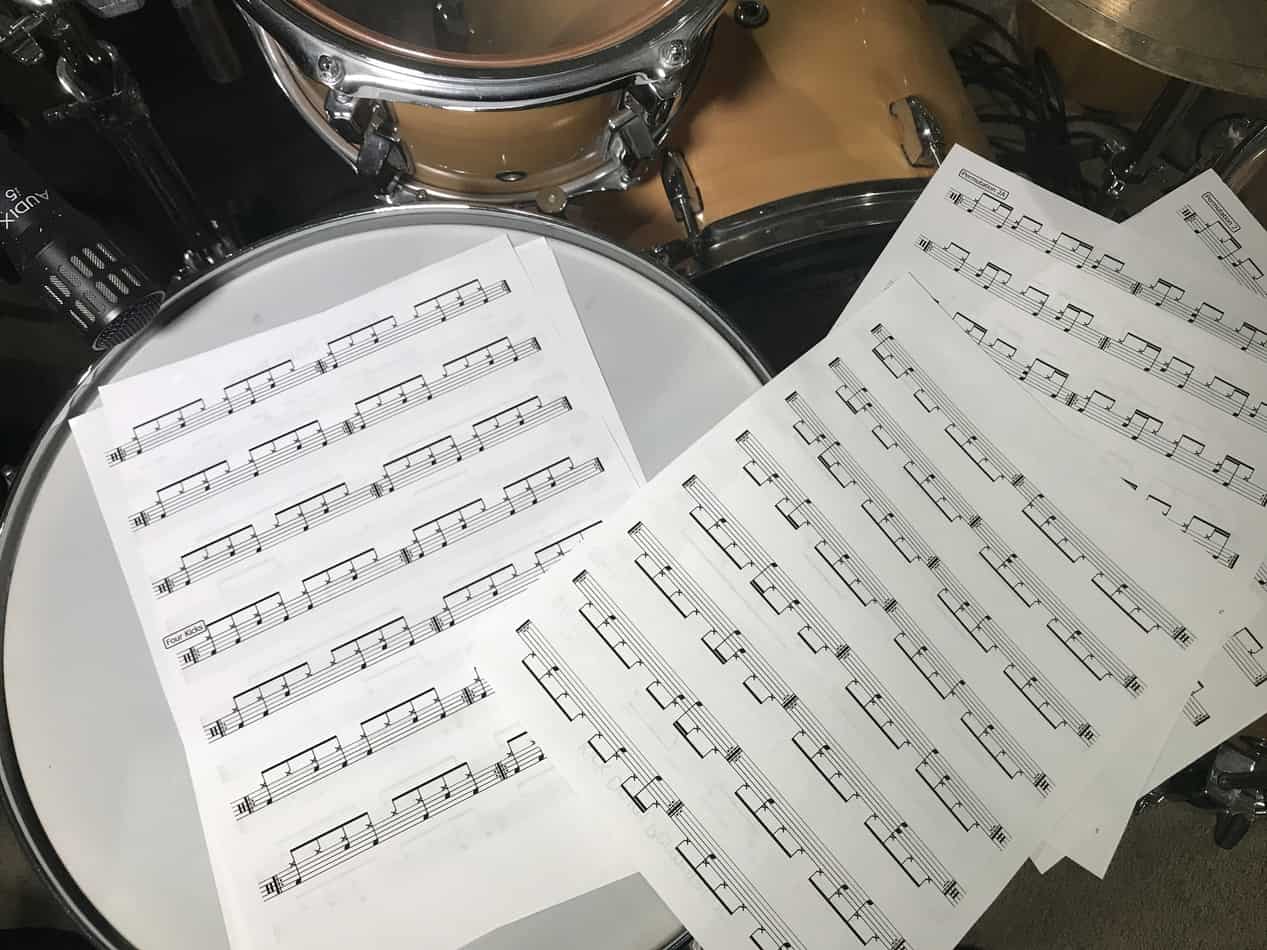

Most of the time, songwriters get together with other writers to gain some input on a song and to hear roughly what it could sound like. I’ve found that playing drums during these sessions gives me an edge on writing drum beats because I can stockpile ideas if I need them later. I can’t tell you how many times a producer has asked me to change the beat while the clock is ticking on a recording session. These stockpiles of ideas become the reason you may get the call for the next session.

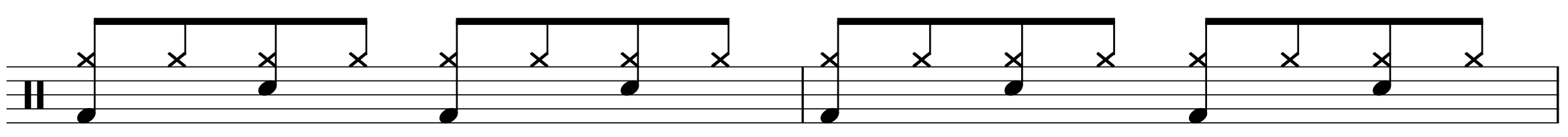

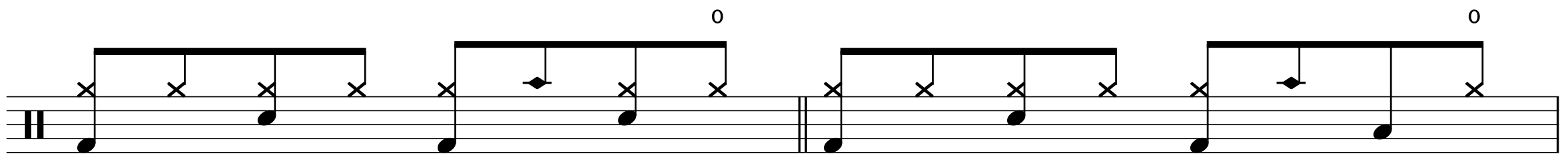

1. Play the “Money Beat.”

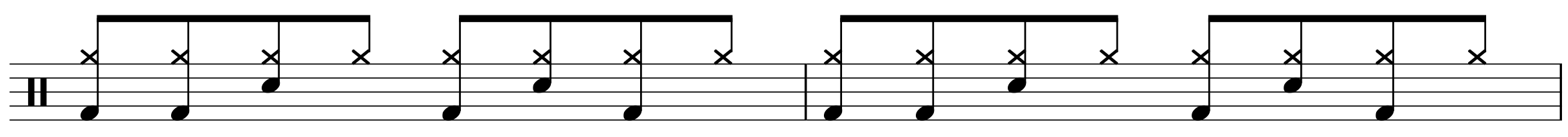

I guess it’s the money beat because you can make a lot of money playing this basic groove on almost any song. This sort of nickname reeks of the Nashville studio scene — not that it’s a bad thing. But there’s truth to how well it has worked Over the years on so many albums.

The beach consists of a kick drum on beats one and beat three, and the snare drum is played on beat two and beat four. The hi hat or any other symbol plays eighth notes on top of the kick and snare. It’s common for players to try different variations on the hi hat or a symbol of rhythm. For example, you may try accented eighths with an accent on the downbeats or the upbeats.

Try it on your song. It’ll probably work.

Related: Drum Patterns – 3 Tips for Writing New Drum Set Grooves

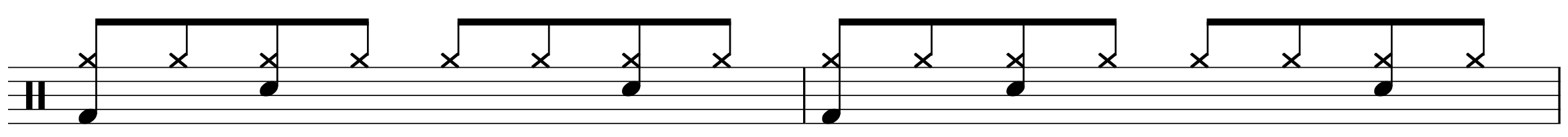

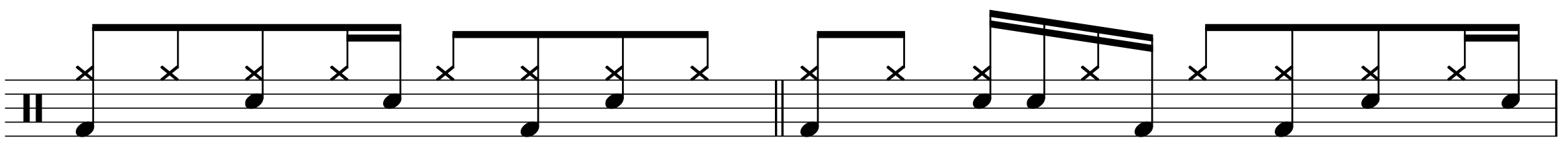

2. Take away a kick drum.

Playing too many drums in a groove is a common mistake made by inexperienced players. Even though I have a lot of experience professionally, I still have to fight the urge to kick everything that I hear. It’s simple yet effective — choose a kick drum to leave out.

By leaving out kick drums in significant places, you may find yourself writing drum beats that allow the music just enough space to develop on its own. Let’s stick with the money beat. If you leave out the kick drum on beat three, you may hear that the guitar and bass rhythms carry that part of the bar well enough for the intro of a song or the first verse. The simple omission of a kick drum then allows you to add it later and make the song feel that much heavier when it needs to.

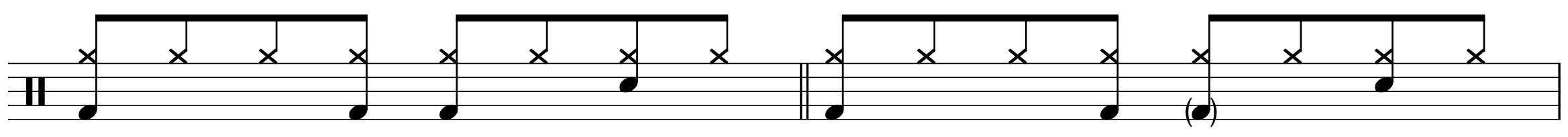

3. Take away a snare drum.

Snare the full back beat on two and four for the chorus or another heavy climactic part the song. Try leaving out the snare hit on beat two. This leaves space to write a kick drum rhythm that’s more interesting than the go-to “boom-boom-chick.”

Also try playing beat two on the snare and leaving out the snare hit on four. If the song phrasing makes sense, you could leave out the snare entirely for the following bar. This makes the snare more of a phrase marker than a groove accent. Either way, it’s totally cool to leave out a snare hit. I think listeners will listen more attentively to your snare drum if it’s not wacking their listening experience every other beat.

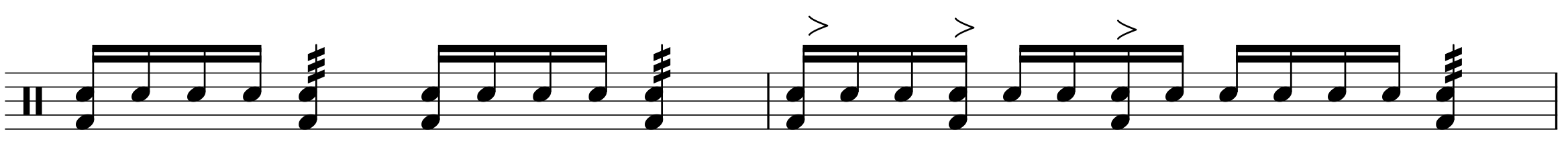

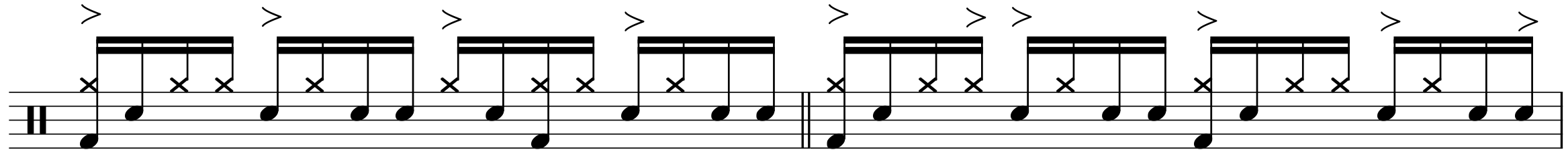

4. Double the guitar or piano rhythm.

Sometimes the rhythm parts of the chordal instruments, like guitar or piano, are crisp enough to receive snare hits right on top of them. You’ll want to try kick drums, too, but avoid smothering the other rhythm section instruments.

Write drum beats that bring out the most interesting rhythms and voices of a song. Too many kick drums or snare hits can create clutter and lack clarity. One way to avoid malicious drumming is to ask yourself how much you are enjoying the guitar part while playing yours with it.

If the guitar accents are eighth notes on two-and, the snare drum could easily play those accents. You’ll also need to consider balancing the other parts of the groove, which could mean considering some of the kick drum ideas I mentioned in number two or cymbal changes I’ll explain in number five.

This example is a basic outline of the snare accents from the drum beat on Elton John’s “Honky Cat.” It’s missing the inner beats and some kicks, but the highlights the idea of playing the snare with the chordal rhythm instruments.

5. Change the Cymbal sound.

Trying different cymbals while writing drum beats can range from simply switching from hi hat to ride or switching out one cymbal for another. It can also mean making a totally new Cymbal sound by stacking cymbals or using China’s and splashes in your remote hat.

The rhythms and combinations of short and long notes should be tried on all of these cymbal possibilities. Try straight eighths, broken eighths, and a variety of accent patterns. Play the shoulder of the stick and the tip in deliberate ways on various areas of the cymbal. Explore the combinations on different cymbals, and the sounds you can produce may as well be infinite.

6. Add a syncopated snare drum hit.

Whether you move the snare hit over a sixteenth, an eighth, or more, the groove will open doors for funkier grooves. Experiment with this approach on both halves of the bar to listen for what works with the other rhythm instruments. Sometimes you can shift a snare to line up with a guitar accent and shift a kick to support the bass line.

Also, try adding a snare drum hit after your backbeat. Any of the three sixteenths following beats two or four can add the funk without losing the rock. But don’t over complicate the groove because you’re trying to be funky. Some of the best funk grooves simply add an eighth-note snare accent after a backbeat

7. Play a march.

I’m grouping a lot of possibilities into this one. The march could be anything from a train beat to a highly sophisticated groove like the one Steve Gadd plays on “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover.” As long as the snare drum is the main groove element, I’m considering it a march.

On the train beat side of the range I mentioned above, you can do a lot with various accent patterns. Placing an accent on beats two and four establish a conventional backbeat, but I would recommend thinking that those accents are always necessary. Try clave accent patterns while filling in with sixteenths on the snare. Or, maybe you want the accents on two and four with an accent the sixteenth before beat four to put a little lift in the anticipation of the beat.

The other side of the range, more toward the Steve Gadd groove, is where I’m hearing Carter Beauford play around with flams, buzz rolls, and drags. This groove is more like what people would think when you say, “Play a march.” The Dave Matthews Band song that comes to mind is “Lie in Our Graves.”

8. Support the backbeat with a tom.

The most trouble I’ve had while writing drum beats was on a Daybreakers song. The producer could probably sense that this song’s groove was not as confident as the others, so he spent extra time on it with me during pre-production. It’s not always fun to be told what to play, but it’s part of being professional. Luckily, this producer new his drummers well and simply said, “Support some of those snares hits with a tom like Steve Gadd.”

All it took was a rack tom to support the snare hit on beat four and a floor tom for beat four of the next bar. This fit so perfectly with the phrasing of the guitar and bass lines that the tom and snare combination is a key voice in the verse sections. That’s all I ever want for my grooves – for the drums to be as important melodically as they are rhythmically.

9. Add percussion to your groove.

Writing drum beats with percussion can be as subtle as a tambourine hit or as obvious as a cowbell or shaker that takes the place of the hi hat or ride. The tambourine hit can be support of other drums, like the snare, or it can be part of a more linear pattern in relation to the other drums.

Try playing the tambourine one eighth note before the snare (or tom) hit on beat four. It anticipates the backbeat and fills a space in the groove that sometimes needs a more interesting sound. If it’s cowbell, then consider playing upbeat patterns or sixteenth note accents and taps on the up beats to make it funkier.

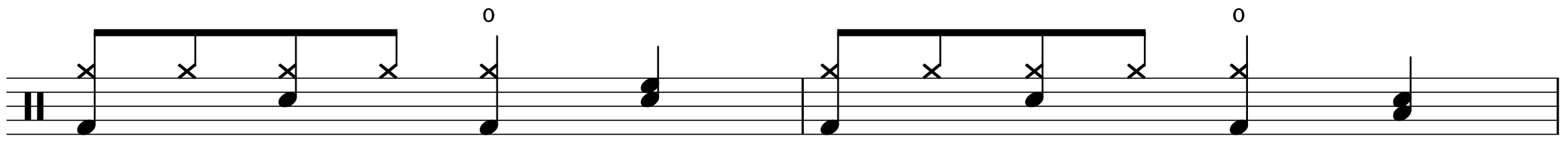

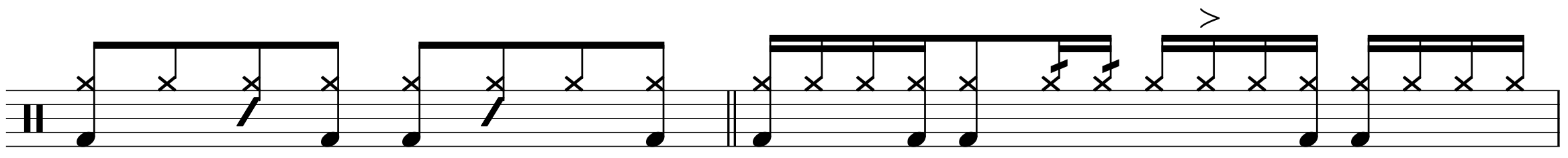

10. Play hi hat slurps in key places.

Slurps are always effective phrase markers. It’s one of the things I do when learning a new song and writing drum beats because it can help me find the phrases that need support as well as those that don’t.

Often, the slurps sound good on an upbeat before a kick or snare. I tend to place single slurps toward the end of the phrase and experiment with them near the beginning only if it seems like it would add to the song.

They can also be played more frequently as part of almost every beat in the pattern. The disco beat, as it is often called, works for a variety of song styles, especially if it makes you want to dance. Turn the slurps around to the downbeats, and you have a completely different groove – something you may hear Carter Beauford play.

11. Paraddles make it funky.

David Garibaldi is the first drummer who comes mind when I think paradiddles and grooves. His approach to accents and taps on both the hi hat and snare drum are, to me, the easiest way to become articulate on the instrument.

Writing drum beats that don’t sound like everything else is easy when you add paradiddles into the equation. You can start with simple paradiddles with your leading hand on the hi hat and the other on the snare. But it’s also very cool to start the paradiddle at different places in the groove or play with where the accents fall.

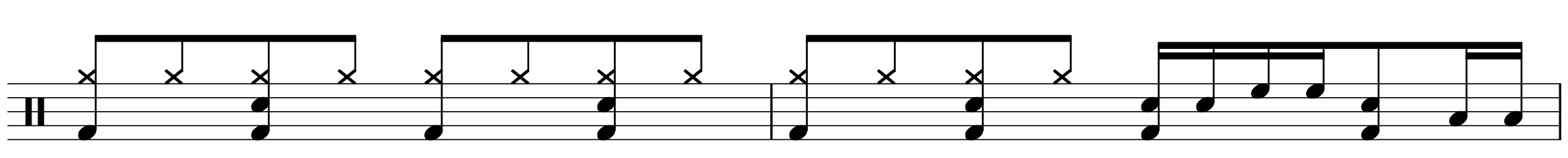

12. Four on the floor drives the groove.

This one is a no brainer. The important lesson I’ve learned is how funky this groove can be even though it’s so downbeat heavy. It supports heavy dance songs and let’s the other rhythm instruments speak for the funkier grooves.

Keeping the kick going through your drum fills was something I learned playing with Bubba Hernandez, a Latin rock polka king. If the kick drops out, the whole groove falls apart. You can get away with filling in between ensemble figures and kicking the hits with the band, but it’s very awkward otherwise.

13. Incorporate Latin rhythms.

The samba bass drum pattern is one of the most common Latin rhythms I hear. It works on every style of music and leaves so much opportunity elsewhere on the drum set. For example, I particularly like adding a cross stick on beat two and the and of three while writing drum beats.

I also like the Baião rhythm from Brazil. It’s a very common kick drum pattern, and, like the samba bass drum, it works for almost any style of music. Try writing drum beats with this kick drum pattern and a sixteenth-note hi hat rhythm only. Add snare hits and time in different places to develop the phrasing of the song within the groove.

14. Change your snare drum sound.

Changing your snare drum sound may inspire you enough to write a drum beat that you wouldn’t have otherwise. Add a splash cymbal to your snare, a shirt, tambourine, or an old drum head (inverted), to name a few.

Check out this article for how to get 10 snare drum sounds.

The nice thing about changing the snare sound while writing drum beats is how it makes almost every beat sound completely different. This means you can reuse beats on an album without making things sound so redundant and usual. Sometimes the “money beat” works for several songs, but a different snare sound may be all you need to change it up.

15. Layer your drum beats.

This one goes well with changing your snare sound and adding percussion because the contrast in the different drum sounds and timbres makes it easy to mix a thick drum sound. It also allows you to live in both the worlds of complexity and simplicity.

If you’re writing drum beats and feel like what you are coming up with is not big enough for the song, layering grooves with different sounds and rhythms can be a game changer. I like to treat one groove like it’s a drum machine and play more live acoustic drums over the top during key phrases of the song. While overdubbing, take this opportunity to add fills and cymbals with the live drums, too.