My first pair of sticks for drum set were Zildjian Vinnie Colaiuta signature series. They were similar to a Vic Firth 5A, and I think he also had a signature stick that was more like a VF 5B. I was 11 years old and had no idea who Vinnie Colaiuta was.

Vinnie is one of the most recognizable modern drummers. He’s performed on albums by composers that changed popular music — people like Frank Zappa, Joni Mitchell, Sting. Since the Internet is full of his interview transcripts and videos of clinics and other performances, so I decided to pull out some of his more profound tips about being a great musician.

I found out who he was my freshman year in high school (1995) when my drum set teacher let me copy a VHS. The tape had the recording sessions for the Burning for Buddy album, a bunch of Steve Gadd live footage, a Billy Cobham clinic, and Vinnie Colaiuta’s Zildjian Days appearance from 1984.

Not even knowing how important Vinnie was to drumming and music, I was drawn to his energy and approach to the drums. This appreciation continued into college where I studied music, and the Internet opened new windows into the minds of my heroes like Vinnie via the readily available interview transcripts.

It’s cool to think about how players develop their ideas over the decades, which can be seen in the way they answer similar questions or use the same stories to answer different questions. I pulled out some of the bigger themes from those interviews and clinics to share with you.

1. “Thought is the enemy of flow.”

Rick Beato recently interviewed Vinnie at NAMM. When Rick asked him to talk about flow, Vinnie replied, “Thought is the enemy of flow.” He explained that there are no mistakes … only creative events.

I love this way of thinking because it takes away the contrived feeling that sometimes players convey. These performances almost always serve themselves and not the music. Vinnie talks extensively about being yourself and playing parts that are best for the music.

This is exactly what Dan Hearle used to teach at North Texas. Dan once told us in lab band that if you think to play something, you probably shouldn’t be playing it.

Both Dan and Vinnie espouse the importance of practicing to develop your flow and to let the ideas flow by developing a vocabulary on your instrument. It’s through this vocabulary that you can engage in dialogue with other musicians (see number 4).

2. Think of odd meter in groupings of two and three.

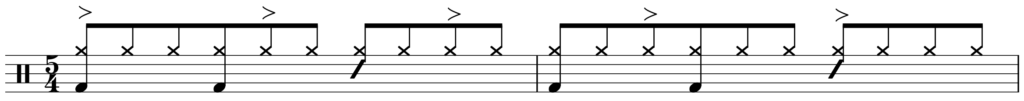

Vinnie talked about his approach to odd meter in a clinic video as well as an interview. Both times, he mentioned that he thinks about odd meter in groupings of two and three. I felt so relieved when I heard this because I almost felt like I was cheating by approaching it that way.

He takes it to the next level with across-the-barline phrasing on the ride or hi hat, which makes it feel less odd. This is a character of his grooves on Sting’s Ten Summoner’s Tales. For example, “Seven Days” is in five with a phrase of four accented on the hi hat and ride. The accents come around every two bars and line up well at the end of the second bar to make a smooth transition.

3. If you practice, things will reveal themselves to you.

Vinnie discusses this issue with Rick Beato in the context of coming up with new ideas, which certainly relates to the first tip on this list. It’s simple. Practicing helps you work out your vocabulary and build those ideas so that they are ready to call up as you play. But what he’s actually referring to here is the “magic” that happens when you aren’t held back by a lack of technique or repertoire development.

I can remember getting to college and completely reworking my technique on the pad and drum set. This led to months, even years, of struggling to execute ideas fluently. It wasn’t until I began playing with several bands, ensembles, and doing sessions that the fluency of ideas began to surprise me.

“The surprises are why I continue to practice.”

4. Listen to other players and have a “fearless dialogue” with them.

Some of this fearlessness comes with maturity and preparation. Most of the best players do not look for mind-blowing ability in other musicians. They look to connect. Making these connections with them is easy if you listen to them, too.

Vinnie talks about connecting with Sting as their professional relationship developed. He said that Sting was good at listening to the band and guiding the group to support the music in the ways he envisioned as a composer. Vinnie said it was a matter of learning what kinds of drum fills he was looking for and adapting, which is hallmark ability of good session players.

I think that the fear of making a mistake is a mistake itself. Fear is a liar. You believe things from it that are not true. The best way to recover from a mistake in the music is to not make it over and over. That would be a deficiency, and no one wants to listen to that or have a dialogue with it.

5. You play who you are.

Victor Wooten talks about how he gets inspiration from his life. He doesn’t separate being a dad or a friend from being a bass player and composer. Vinnie gives off this same vibe when he talks about playing who you are.

As Rick Beato commented in an interview, Vinnie’s responses to questions are interesting and well organized, like his playing. The people who know you and know how to appreciate music will know if you are coming across in your performance.

One of my interests is learning the stories of what makes musicians and groups successful. When it comes to touring groups, I often hear a common theme about the players who do well on the road. Not only are they prepared and interesting to perform with, they are nice to people and easy to be around for sometimes months at a time.

Some of my favorite musicians are my friends. This isn’t because I know a lot of great players. It’s because a lot of my friends are also great players. What makes them my favorite musicians is how their personality comes out in their playing.

6. Play for the Venue.

Arenas need to be approached differently than theaters. “In theaters,” Vinnie says, “… you can stretch out.” You have to play for the distance of the sound traveling to the audience. Otherwise, your performance can lose clarity in the distance the sound travels with sometimes accumulating effects.

I first encountered this with Bubba Hernandez at some of the festivals we played. It was the first time I had played for thousands of people, and my instincts kicked in to water down the parts to only the most crucial rhythms and accents. It allowed me appreciate the intimacy of a small coffee house gig in a whole new way.

The only time the venue didn’t matter as much was with a country band that had in-ear monitors and close mics on everything. Every show sounded the same to me. I still looked to the audience to play things that connected with them, but I don’t remember the size of the venue playing much into those gigs.

7. Enjoy your practice time.

Vinnie got this advice from Billy Cobham, and I wish someone had told me to enjoy my practice long ago. I didn’t start enjoying my practice until the practice assignments were more guided by my own goals.

Tips for enjoying your practice time (from Rhythm Notes)

- Play along to your favorite music.

- Envision yourself being successful with the thing you are struggling to master.

- Transcribe your favorite drummers, and reflect on the nuances of their playing.

- Learn a new style of music. Step out of your comfort zone. Try polka if you play metal, for example.

For more about practicing, check out this article about everything you need to practice drums.

8. “When you play a groove, you have to understand its character.”

Changing from one style to the next as well as between time signatures is important to do well and smoothly, but it’s important that you serve the groove. Vinnie doesn’t explain this much in the Berklee Press interview (2001), but I’ve read enough of his interviews and watched enough clinics on YouTube to know that he is talking about connecting with a song emotionally and respecting it on an essential level.

This goes back to number five in this list — play who you are — which is clearly a theme of Vinnie’s approach to music.

I used to go to the Greenhouse in Denton Texas to listen (and play) jazz every Monday and Thursday. This went on for about two years before I learned the lesson Vinnie is trying to communicate in these interviews.

It took me time to meet and hang with the players — to get to know them — before I could really appreciate how their music was an extension of their personality. Once I figured that out, I was playing with a variety of bands almost weekly at my favorite jazz club.

9. “It can be healthy to learn about someone’s style.”

With all of the emphasis on being yourself and playing in a way that identifies you, Vinnie admits that learning someone else’s style can be good if their style offers some value. He cautions spending much time emulating other players to the extent that you don’t develop who your are as a musician.

Notice that Vinnie says “can be.” This implies that you need to be careful about how emulating other players can negatively affect your style. After studying a Tony Williams transcription, for example, I usually put it away for years and study something else for a while like shuffle feels from a bunch of drummers (i.e., Jeff Porcaro, John Bonham, Jim Gordon).

This is another tip that ties in with number 5. Play who you are. My wife rarely comes to see me play, which isn’t her fault. If I played 150 shows in a year, she was able to attend three or four. I knew I was playing my own style when she found the festival stage I was playing on because she said it sounded like me in distance.

10. Don’t blow your chops.

During a 1989 clinic in New Jersey, Vinnie shared a story about hanging out with Jim Chapin. He said they played a lot on the pad before he had to go on stage to perform. When he couldn’t pull off his ideas around the drums, he knew he had blown his chops.

Warming up is one thing, but using all of your energy and wearing out your chops before performing is a bit sophomoric. Playing rebound strokes on a pad for at least 15 minutes before performing is crucial to sustaining a busy performance schedule.

I went through a time when I didn’t warm up (or practice) like I should have, and I paid for it. One day, my wrist sounded like an old creaking door. I had gigs booked and rehearsals, so I let it rest most of the time and played with a brace on my right wrist for two weeks on the road. I eventually recovered and will never take my warm up for granted.

Final Thoughts

Vinnie is in my top five favorite drummer list. It’s a tough list to think of because there are so many awesome players who are also great people. Vinnie is easily one of them.

What’s your favorite tip on this list? Let us know in the comments, and tell us how it has helped you level up your drumming.

Sources

Rick Beato interview

Modern Drummer interview 1993

Various drum clinic videos available on YouTube